By Nicole Valentini

On an autumn night in 1994, the Taliban were getting ready to conquer Afghanistan. Only two years before, a terrible civil war had broken out among the different Mujahideen factions that had defeated the short-lived pro-Soviet government, turning the country into a wasteland of terror and despair.

At that time, in a small village in Ghazni province in central-eastern Afghanistan, Asharaf Barati, a 13-year-old boy from the Hazara ethnic group was having his final supper with his family. Even if his mother didn’t express it, she knew she would not see her son again for a long time—possibly ever. The boy’s departure was set for dawn. His uncle was to pick him up and take to the smugglers.

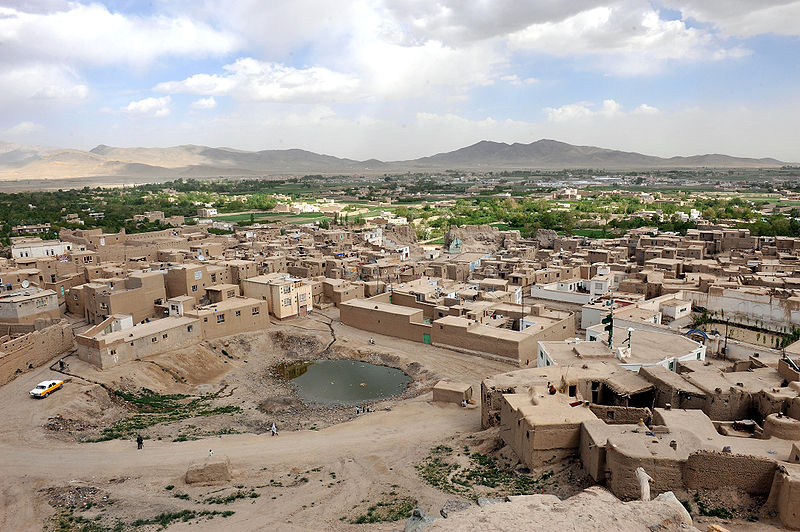

Ghazni, Afghanistan. Photo by ISAF Headquarters Public Affairs Office. Members from Ghazni Provincial Reconstruction Team visited Old Ghazni City April 18, 2010, located in Ghazni Province, Afghanistan. (Joint Combat Camera Afghanistan; Photo by Tech. Sgt. James May). CC-2.0

Abdul Ali Mazari, the leader of the Hazara-dominated Hezb-e-Wahdat political faction had just been assassinated by the Taliban, and many Hazaras felt suddenly vulnerable. The Taliban, renowned for their hatred of the Hazara, was closing in. Hazaras were leaving the country en masse, some for Pakistan, others for Iran.

Days after his escape, Asharaf found himself in Pakistan. For a few years he worked in a coal mine, a job that left him sick and exhausted. After that he took his meagre earnings and went to Iran, where he found himself once more in a foreign land among other refugees, carrying mortar sacks heavier than himself for a living. Then, as now, the plight of Afghan refugees in Iran was one of hardship and exploitation.

“It was a tough situation,” recalled Asharaf in an interview with Global Voices. “We (Afghan refugees) were living in the empty building site we were working on, there were no services and no heat, we put some nylon on the open windows to try not to die from cold during the night.”

After four years, Asharaf left his undocumented life in Iran behind and readied himself to travel to Europe. Following a perilous journey by sea, he found himself castaway on a tiny, uninhabited Greek island. In 2002, after being turned down for asylum by the Greek authorities, Asharaf finally reached Italy.

Asharaf wandered the streets of Rome for a while, homeless, sleeping in parks and having meals in a church that distributed food to the less fortunate twice a day. While it is true that Italy has become something of a second-chance destination for failed asylum seekers due to relatively high approval rates, it is also true that the conditions into which asylum seekers are received are dire. According to the NGO Civil Liberties Union for Europe, “the system suffers from a general lack of transparency. The huge majority of asylum seekers is hosted in the more than 3000 ‘extraordinary reception centers’, which are improvised structures in the hands of unqualified and unprepared staff.”

According to Italian law, asylum seekers can access accommodation centers only after they are formally registered, a process that can drag on for months after an asylum application is initiated. During this period, people who can’t afford to pay for accommodation must seek recourse to friends’ hospitality, or resort to sleeping rough.

This is the fate that befell Asharaf.

But his irrepressible spirit prevented him from being down and out for too long. After years working in various jobs in the construction sector, Asharaf poured his savings into a establishing a hostel in Venice. It was such a success that after a while he opened a second hostel and a takeaway restaurant.

Asharaf Barati’s story is now the subject of a documentary called “Behind Venice Luxury – a Hazara in Italy”, directed by Amin Wahidi. The film won the 24th Venice City Award in 2017.

Asharaf Barati in front of”Casa Fiori”, one of the hostels he owns in Venice. Photo by Basir Ahang. Used with permission.

In Italy, entrepreneurs, especially those who are not Italian nationals, face an uphill battle. Red tape, high taxes and access to credit are among the major obstacles.

According to an unofficial estimate, there are around 20,000 Afghans in Italy. For many the country is a stopgap option en route to other European destinations. But in recent years a number of Afghan-run businesses have sprung up, including tailoring establishments, travel agencies, hotels and restaurants. Some Afghan restaurants have won acclaim in the Italian press for their excellent cuisine.

In Venice there is the restaurant Orient Experience, the brainchild of Hamed Ahmadi, where the waiters and kitchen staff are mostly refugees from various parts of the world. They tell the story of their journey to Italy through Afghan, Iraqi, Turkish and Greek dishes on the restaurant’s menu. Afghan entrepreneur Ali Khan Qalandari has established a new restaurant in Padua called Peace&Spice, and Afghans are also behind the Kabulogna pizzeria in Bologna and a Sushi restaurant in Rome.

But Asharaf’s own ambitions stretch far beyond the Italian hospitality and retail sectors, back to the land he left under duress as teenager.

“Where there is risk there is opportunity,” Asharaf says with a smile. “I want to invest in Afghanistan, I have never forgotten my country and I can’t live happily knowing that my people are suffering. I am planning to start a project for the farmers of the poorest provinces of the country, especially women. They comprise half of society and must have the same opportunity as others.”

Asharaf also has plans to open a factory in Kabul where people can to learn packaging and conservation practices. “In this way,” he says, “they will be able to sell their surplus products to the market and improve their financial situation.”

The journey of the successful entrepreneur follows a path from insecurity and doubt to stability and prosperity. Having made that journey himself, Asharaf now wants to help Afghanistan make it too.

Source: Global Voices